What's the Difference Between a Rhodes and a Wurlitzer?

The Rhodes and the Wurlitzer are sometimes mentioned interchangeably, but they’re actually pretty different. We do spent 99% of our time around electronic pianos, but trust us: it’s not just our bias talking. A Rhodes and a Wurlitzer sound different, feel different, and were invented in completely different contexts. Most studios would benefit from one of each. (Well, one Rhodes and two or three Wurlitzers - but now this might be our bias talking.)

Here’s a breakdown of some of the major differences, starting with the most practical differences between the keyboards. The final points are a few historical reasons that explain why these differences exist.

Both instruments have their own characteristic sound. The Rhodes has a smoother, more bell-like tone, while a Wurlitzer has a distinctively harsher edge. This is particularly true when the Wurlitzer is played aggressively (that’s the famous Wurlitzer “bark”). For this reason, a Rhodes can often be mixed into a song with a little more subtlety.

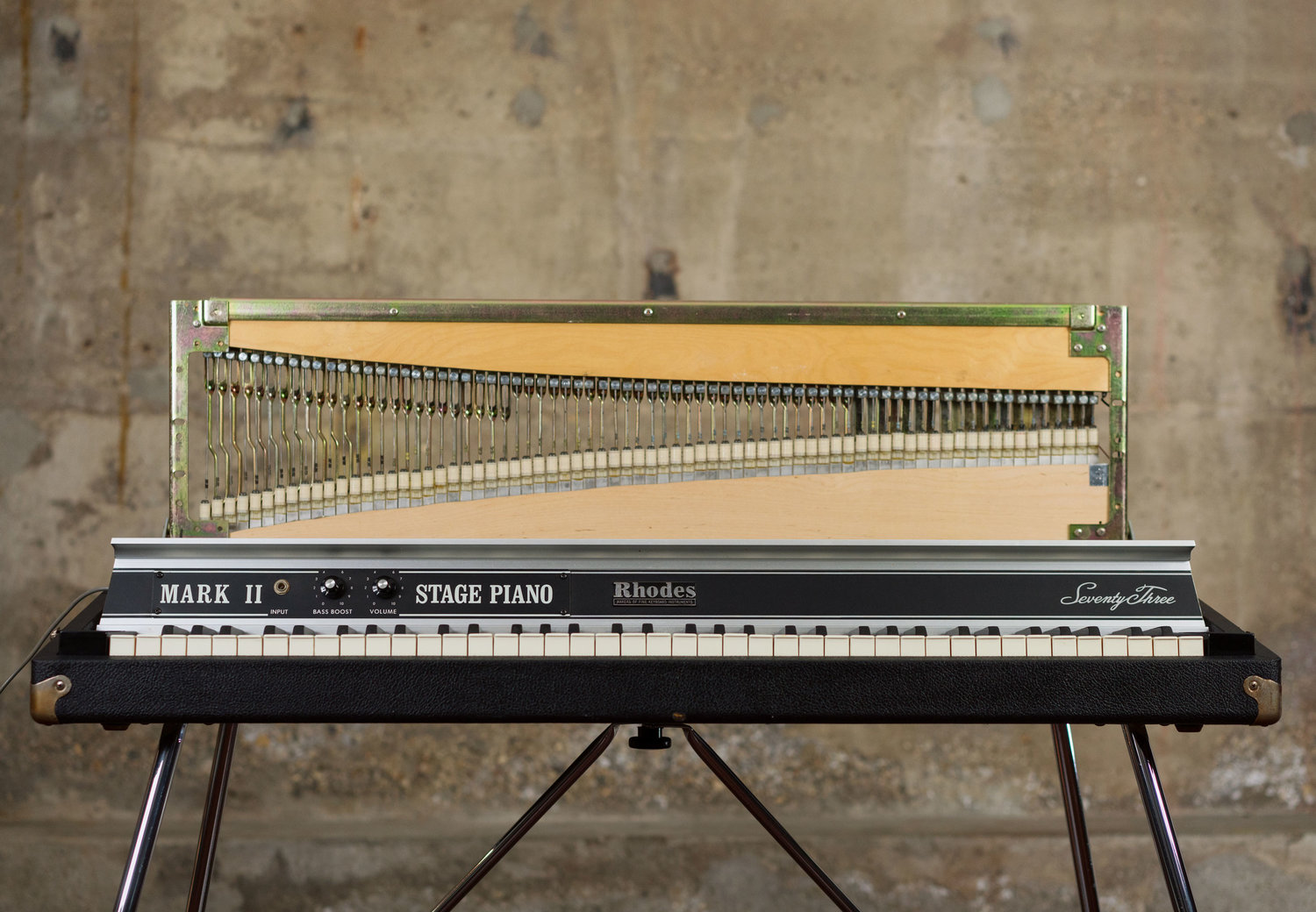

The Wurlitzer and the Rhodes have a different method of tone generation. The Wurlitzer uses reeds, and a Rhodes uses tines. Tines are interchangeable between different models of Rhodes, but early Wurlitzers cannot use later Wurlitzer reeds. Rhodes tines are also much easier to tune than Wurlitzer reeds. All you have to do to change the pitch is to move a spring up and down the tine, while a Wurlitzer requires adding to or subtracting from a blob of solder at the end of the reed. However, Rhodes tines tend to rust easier, so it is more common to find a Wurlitzer with reeds in good condition.

Enjoying this article? Subscribe to our newsletter for weekly repair tips & other vintage amplifier & electronic repair content!

The Wurlitzer has an onboard amplifier, while the Rhodes must be connected to an external amplifier. The suitcase Rhodes is an exception: this model is mounted on a speaker cabinet that contains an onboard amplifier. Some Wurlitzer models have an aux output, but a signal cannot be taken directly from a Wurlitzer’s pickup, because it’s a special type of pickup that requires a polarizing voltage to work. On the other hand, a Rhodes has magnetic pickups like a guitar, so its signal can be taken right at the source and sent to any amplifier.

The Rhodes is a lot heavier than a Wurlitzer. The “portable” model of Rhodes actually weighs the same as a console Wurlitzer. The Wurlitzer 200a is around 70 lbs lighter than the comparable stage Rhodes. In a studio, this isn’t too much of a concern, but if the keyboard is intended for gigging this is definitely a consideration.

Rhodes are available with up to 88 keys, but all Wurlitzers have just 64. The Rhodes comes in 54-key, 73-key, and 88-key versions, as well as an early rare Piano Bass version. All Wurlitzers (except for the very rare 106 student models) have 64 keys. This is plenty of range for many applications, but some musicians may require a keyboard with more available bass notes.

Wurlitzers are often considered more comfortable to play than Rhodes. Wurlitzers have a more sophisticated mechanical action than the Rhodes, probably because Wurlitzers were made by a piano company while Rhodes were made by Fender, a guitar company. Two things about Fender. First of all, this is a company that found success by inventing the Telecaster, basically a slab of wood with pickups, while its competitors were entangled in the mistaken idea that electric guitars had to have exactly the same level of craftsmanship as acoustics. Second, during the years that the Rhodes was manufactured, Fender was owned by CBS, who notoriously cut corners anywhere possible. So, Fender was a company with a long-standing culture of simplifying things - first, in a laudatory lean-startup way, and later in the classic selfish corporate-greed way.

In contrast, Wurlitzer clearly invested research into their electronic piano action, because it actually improved over the years. Later Wurlitzers are more reliable and more easily serviced than the earliest models. On the other hand, Fender made more and more parts plastic. This isn’t strictly a bad thing - plastic doesn’t warp, so many late Rhodes are very playable even after years of storage - but it certainly doesn’t help the Rhodes feel like a traditional piano.

The inventors of these two instruments were guided by two different design principles. Many of the differences between Rhodes and Wurlitzer make perfect sense when you considered who was behind the design of the two pianos. The Wurlitzer was invented by the Wurlitzer Company, an acoustic piano manufacturer that was constantly searching for ways to make pianos more affordable and convenient to own than ever before. Because they already made pianos by the hundreds, Wurlitzer had all the resources necessary to devise a really good simplified piano action. But they weren’t snobs about tone: in fact, around 50 years earlier, Wurlitzer invented the spinet piano, which was lighter and cheaper but sacrificed a lot of the richness and harmonics of traditional full-sized pianos. During the 1920s and 1930s, spinets brought pianos into reach for a wider range of consumers, but to this day piano teachers rage against them, arguing that their tonal shortcomings give beginners bad habits.

On the other hand, the Rhodes was invented by an individual, Harold Rhodes. Like Wurlitzer, Rhodes wanted to make a more convenient piano, but his motives were not necessarily commercial. (During WWII, he was hired to teach piano to soldiers convalescing in the hospital, so he invented a keyboard that could be played while bedridden. This became the foundation of all future Rhodes designs.) Furthermore, his background as a jazz pianist and music teacher made him something of a perfectionist about tone. It’s possible that he was never truly satisfied with the sound of the Rhodes - perhaps it was that perfectionism, or perhaps it was because CBS was constantly pressuring him to cut the manufacturing budget in ways that compromised the quality of his keyboard. As one engineer at Fender recalls, “Harold was never really enamored with the sound of the instrument. Harold’s goal was to make an acoustic piano so he wanted the harmonic content of the richness of the strings, he wanted the feel of it. It was part of his never-ending quest.”

While Wurlitzer was preoccupied with making the electronic piano feel like a piano, Harold Rhodes settled for making his piano sound as piano-like as possible. He was after that harmonic realism, and anyway, with CBS in charge of the budget, it was likely easier to focus on the tines than it was to keep standards high for every moving part in the mechanical action. So, the Rhodes has up to 88 keys and a more elaborate tone generator that is modeled after a tuning fork. The Wurlitzer has more moving parts in its mechanical section and somewhat more touch-responsiveness, but its piano tone is abstracted to a greater degree.

The Rhodes, in its commercial form, was released 10 years after the first Wurlitzers came to market. This is a significant amount of time, because technology in the 1950s and 1960s moved very fast. If the first Wurlitzer was conceived of ten years later, it is very possible that it would have looked and sounded very different than the Wurlitzers we know today. Solid state electronics were more sophisticated in the 1960s; plastics were more sophisticated; manufacturing was more automated; rock n roll was at its peak and popular music in general was completely different. Despite all this, and although Wurlitzer improved upon their electronic piano over the years, they never strayed too far from the original design. Why would they? They had already invested the R&D, they had all the necessary patents, and they had a history of successful marketing and sales.

However, imagine that Wurlitzer started designing the electronic piano in the 1960s or 1970s. Perhaps they would have tried to design a mechanical action with more plastic parts, which could be manufactured cheaper and more consistently. Perhaps they would have attempted to cater the design to touring rock musicians - or, alternatively, focused on selling more directly to the kids that idolized them. Perhaps the electronics would be designed for more volume or recording fidelity. They certainly would have used a solid state design from the beginning.

This isn’t to say that this hypothetical later Wurlitzer would be better. But it’s worth remembering that Wurlitzer - even the latest releases - was very much a product of the 1950s, from its midcentury styling to its music-teacher-approved mechanical action to its conservatively-designed onboard amplifier. In contrast, the Rhodes was heavily influenced by the music culture of the 1960s (which was inspired, in large part, by Fender gear of the 50s). It has a more resilient exterior, so it can be more easily gigged with. It’s big and heavy and looks great onstage. It can be paired with any amplifier and therefore has no manufacturer constraints on its volume or tone. Its simple mechanical action won’t exactly impress your piano teacher, but it gets the job done.

So, Wurlitzer and Rhodes are drastically different, and it’s not just because of their tone. It’s also because of the culture and priorities of their manufacturers, the era that they were invented, and the consumers that each piano targeted. And the bottom line is this: you need one of each.

Further Reading

Browse all of our articles on restoring vintage gear. Or, click on an image below.