Why We Love Wurlitzers with Built-In Leg Storage

Early Wurlitzer keyboards — the 112, 120, and 140-series — have built in leg storage. The outer lid (which is hopefully still present all these years!) has a space to firmly screw in the legs, as well as a little strap in the center to hold them in place. This is probably early Wurlitzers’ most underrated feature!

We distinctly remember the first time we saw, in-person, this lid. It was attached to a Wurlitzer 112, the first non-200 Wurlitzer we ever acquired. We thought this keyboard was the coolest thing ever. It had (like all 112s, although we didn’t know it yet) this crazy throwback splatter design that looked a lot like old countertops. Some corporate suit signed off on this crazy paint job?! On a product marketed to adults?!?! Yes and yes! (Welcome to the 1950s.) Another thing we could barely believe: how old it was. We drove around like we had ancient Mayan ruins in the backseat.

A Wurlitzer 120 with its lid. Note that this one is in such good shape that it even has its latches.

We weren’t totally wrong about that. Like Mayan ruins, the 112 spoke to us across a vast divide of time and culture. It was saying: I was designed by somebody who cared. Case in point: the built-in leg storage. This was an extremely thoughtful feature that anticipated the way real people would use the instrument. If real people were going to tote this piano to a party or the beach or wherever, they would need a means to carry the legs. Wurlitzer legs are long and awkward, and there is no way to carry all four at once without feeling like an extra in a bad slapstick. They fall out of your hands; they smack into each other. The more gently you try to hold them, the more certain you are to drop them.

In retrospect, it seems like Wurlitzer may have been joking when they said that the 112 was portable. (It weighs about 80 lbs.) They were not, and the built-in leg storage proves just how serious they were. They wanted to ensure that there were no obstacles to you taking your piano out for a jetset weekend with friends. They wanted to prove the instrument’s convenience. They wanted to help you.

When cutting costs, these little details are the first to go. They’re made for the user: i.e., the person who has already bought the product. The user is a person whose needs are fully subordinate to the consumer — the prospective consumer, to be specific — a person who is thinking about buying the product. The user doesn’t have to be buttered-up anymore. They bought the product; the company has their money. It’s just good business to make minor reductions to the user experience, if doing so makes a stronger case to the prospective consumer: for instance, if cutting costs makes it possible to reduce the final price of the item. If you have a strong enough market share, you can even cut costs, keep the price the same, and distribute more profits to your shareholders!! (This is, in fact, the story of the Fender Rhodes’ evolution.)

This Wurlitzer 145 had extremely clean and white keys for its age, thanks to the external lid.

We’re not trying to argue that Wurlitzer was the most ethical company of all time, because they definitely were not. (See the episode where they drove the inventor of automatic harps into financial ruin by reneging on a contract, while simultaneously unloading the excess harps to San Francisco brothels, which were forced to buy them because Wurlitzer had an understanding with the the notoriously corrupt San Francisco authorities. And no, not the autoharps that you’re thinking of — think player pianos, except a harp instead of a piano. These things are lost to the fossil record of obsolete instruments, in part thanks to the financial pressure that Wurlitzer put on the inventor.) Anyway. In the 1950s, cost-cutting wasn’t the same as it is today. Musical instruments didn’t have digital circuits or computer-generated anything. Many of their necessary parts were hand-made or hand-finished by necessity. For this reason, there was a limit to how much you could pare down and still have a minimally functional product.

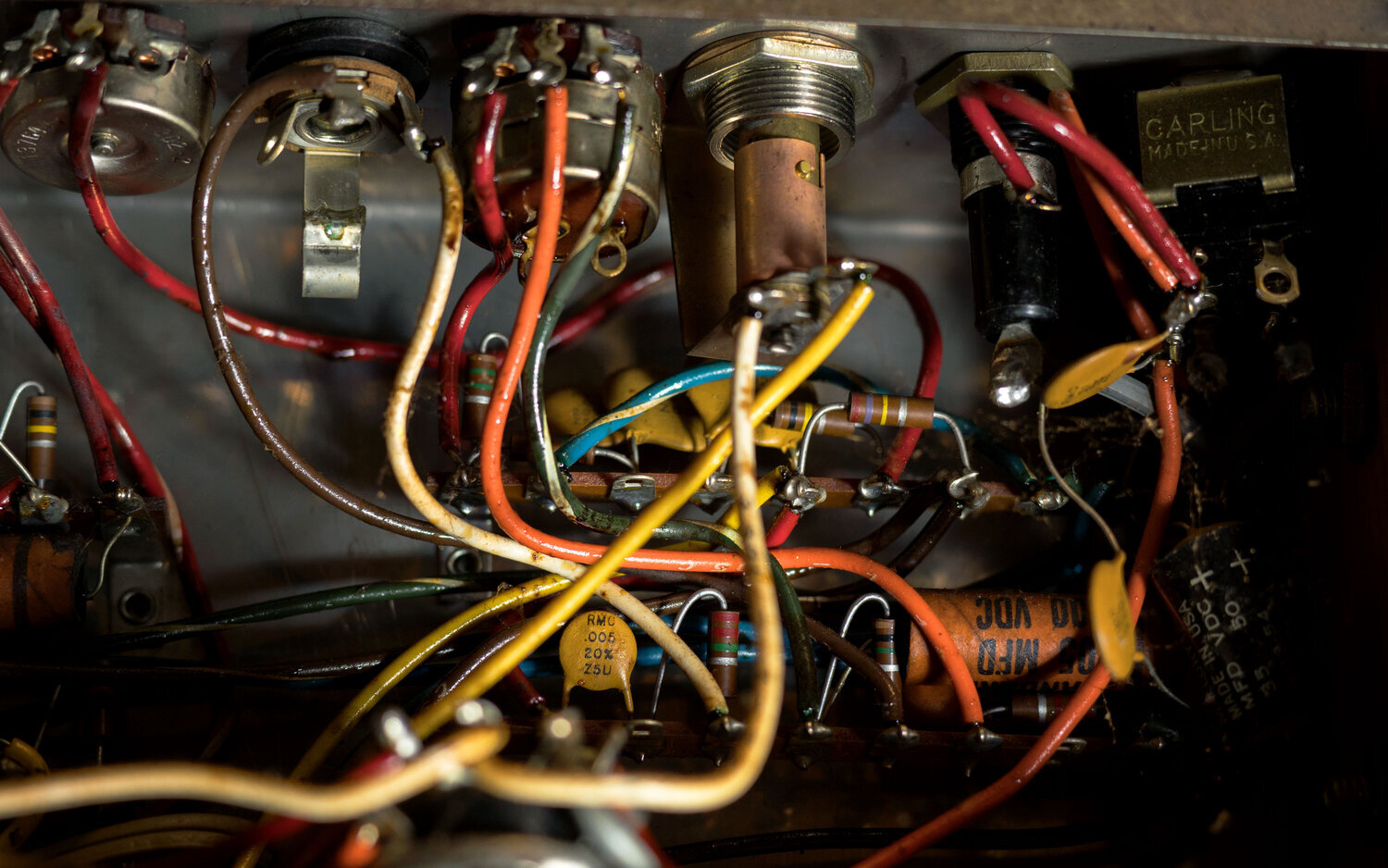

For instance, when amp manufacturers cut costs, they had to keep the tubes, the point-to-point wiring, the screen printed lettering: all kinds of interesting details that, today, would be the very first thing to go. But, back then, there was no way around those things. Transistors required careful engineering; high-voltage tube components didn’t exist yet; digital printing wasn’t a thing. Instead, manufacturers cut costs by eliminating the power transformer, which is of course an extremely bad and unsafe practice, but it underscores the point: often, the only way to manufacture something truly cheap was to make it pretty much unusable.

This 1956 advertisement brags that the Wurlitzer “carries like a suitcase” and then, in the next sentence, admits that it “weighs only 99 lbs.” Definitely a bold way to advertise its portability.

So, in the 1950s, the difference wasn’t necessarily between a product that was expensive to produce and one that was dirt-cheap. Cutting corners was a game of diminishing returns. Because the rewards of cost-cutting were way smaller, manufacturers were more likely to spend the extra dollar and take that extra step to make their products that much more functional. They weren’t tempted by the money-making potential of an overseas production line that would be both incredibly inexpensive and conveniently hidden-from-sight. Nor would they be pressured into it by the practices of their competitors. Outsourcing was an option that didn’t really exist yet.

That culture is gone now, but it was still around in the 1950s, when the 112 was put into production. This keyboard’s leg-storage lid was designed by somebody who cared, because you could still make money creating detailed and thoughtful products. Wurlitzer didn’t just want to sell this keyboard and move on to collect money from the next person. They wanted to convert buyers into believers, and they accomplished this by working thoughtful little gifts into every facet of the design. Hence, legs you didn't need to awkwardly juggle anytime you needed to move the keyboard from A to B.

Mary Healy carrying a Wurlitzer 120 in a 1959 newspaper advertisement.

This was a design philosophy that even Wurlitzer totally abandoned by the time the 200 was released. In the late 1960s, everyone was familiar with electronic pianos, and the culture of cheap mass-production was really starting to ramp up. Wurlitzer didn’t have to work so hard to convince the consumer that portable keyboards were a good idea. So the 200 says: sure, I’m portable, but if you want my legs to come with me, you figure out how to transport them. Sure, there was a carrying case, but you had to pay extra for it, and almost nobody did. (We’ve only seen a handful in all our years working on Wurlitzers.)

Thoughtful, generous design is certainly not the whole story. On some level, Wurlitzer likely felt that they had something to prove. First of all, they were calling this piano portable, even though it weighed 99 lbs (if the ad above is accurate). More fundamentally, they were calling it a piano. If you’ve ever played a 112, you know that it does not exactly feel like playing a conventional piano. It’s a little more clunky, even in fully-restored condition. You really have to familiarize yourself with the weight and movement of the keys before you can play it with any nuance.

In fact, the Wurlitzer 112 was less a literal piano than a vision for the future: one where the piano follows the musicians, and not the other way around. What better way to prove this than a keyboard that neatly folds into itself, four long tapered legs tightly fastened in place underneath the lid? And, with such an elegant method of storage, how could you not want to put it to use? How could you resist taking it everywhere, regardless of the weight?

The 112 — and all Wurlitzers that followed its basic design — was designed to make a musicians’s life easier. And not in a superficial, as-seen-on-TV way, but in a practical, fundamental way. The design of its legs is one example of that. And that’s why we have a soft spot for all Wurlitzers with built-in leg storage.

Further Reading

Browse all of our articles on restoring vintage gear. Or, click on an image below.