Why does my Wurlitzer 112 amp have a weird octal plug that goes nowhere?

What is the purpose of Socket A?

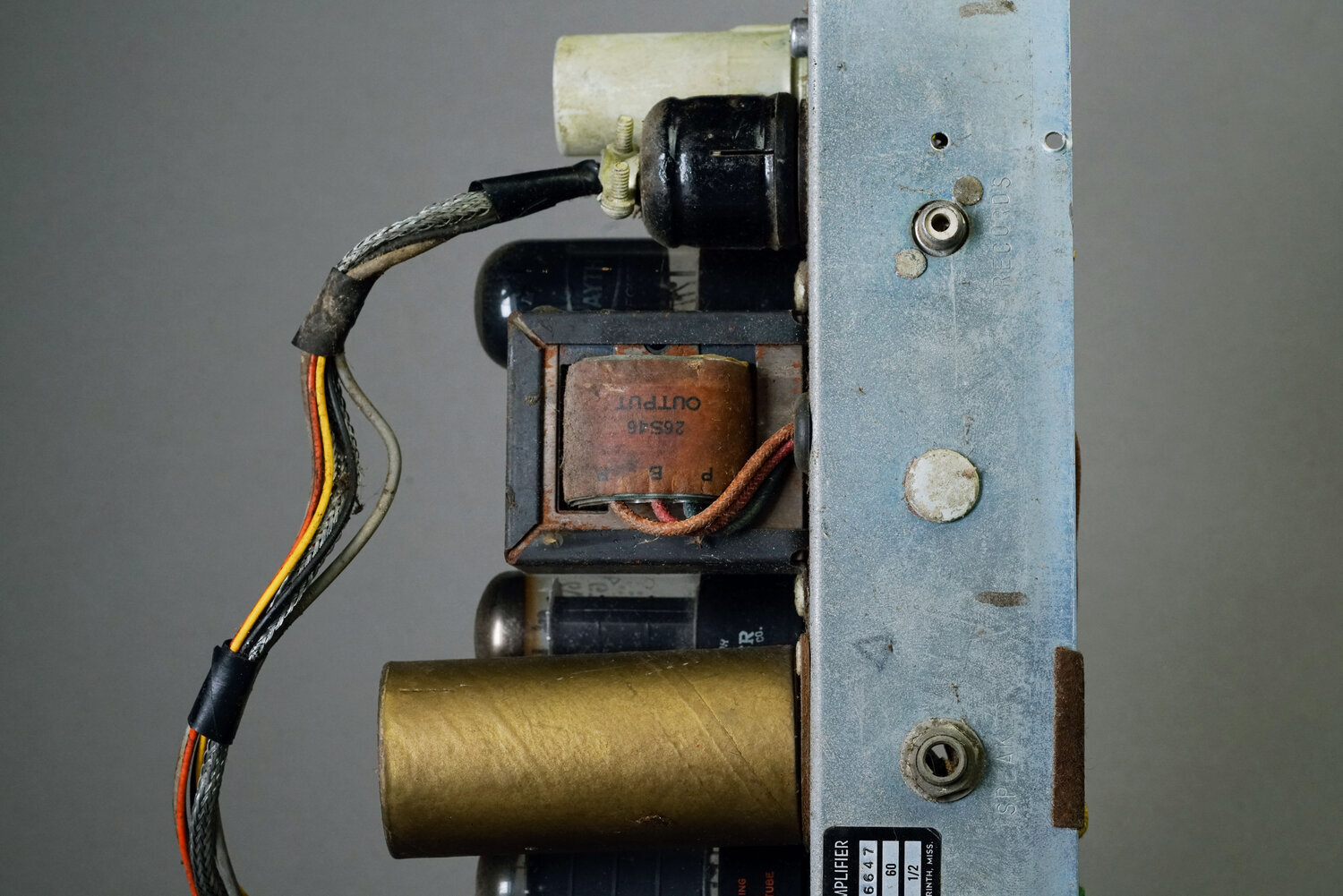

The Wurlitzer 112 has a mysterious octal plug that appears to go nowhere. It is very similar to the wiring harness plug, except that it doesn’t end in a wire. It’s just a little black dome that occupies chassis real estate and doesn’t appear to do anything in particular.

If you consult the schematic, you find that there is a resistor and a capacitor inside the dome — and nothing else. The capacitor is, in fact, a coupling capacitor. Part of its job is preventing DC power supply voltage from entering the next gain stage. Here, its value is 500pf. The resistor is 470k and it appears in series with the capacitor. This only deepens the mystery: why go through all the trouble to make this thing, then only put two very ordinary components inside?

An illustration of the modular tremolo unit that Wurlitzer proposed in patent 2,881,650. Note that the cable from the auxiliary amp travels underneath the main amplifier in order to reach the tremolo controls. The amplifier actually allows for this, since it is elevated from the cabinet by two strips of wood.

The answer is found in an early patent: 2,881,650. Here, we learn that the amplifier for the Wurlitzer 112 was intended to have a modular feature. The user could remove the stock plug, and replace it with a plug that contained the circuitry for various effects. For beginners, those effects would be limited to simple filters that reduced either bass or treble frequencies. More advanced players could attach a tremolo module that allowed the user to adjust tremolo for bass and treble frequencies independently of one another.

“Another feature of great importance is a plug-in shaping circuit, and additional circuits may be plugged in in place thereof. [...] When it is desired to vary the frequency response, such as to produce tones simulating different types of pianos, or even different types of instruments, or to balance an instrument for a particular installation or pianist, all that is necessary is to remove one of the plug-in circuits, and to insert another having different values of either or both the capacitor and resistor.”

Companies often patent inventions that they have no intention of manufacturing. This is because the patent gives them a monopoly on the invention regardless of whether it is on the market or not. With a patent in hand, the company can choose to manufacture the invention later, license it to another company for a fee, or just prevent anyone and everyone from using the patented technology until the patent period runs out.

Detail from the 112 schematic found in the service manual.

So, it’s not unusual that Wurlitzer included a very ambitious feature in a patent that they ultimately didn’t end up using in the piano itself. The crazy thing is that they actually did try to use it. The vestigial plug on the chassis makes this clear.

We know that Wurlitzer ultimately abandoned this modular system for good. There is no information on it in the service manual, no future Wurlitzers have any features like it, and, as far as we can tell, no dual tremolo 112s have ever actually existed in the flesh. But before that happened, Wurlitzer was apparently in deep enough that they designed the modular socket into the regular 112 chassis. And so every 112 bears the traces of the idea: specifically, nestled among the preamp tubes and the transformers and all the other very necessary features of the amplifier, one plug to nowhere. And, in every service manual, this plug is illustrated in meticulous detail, complete with friendly crooked little arrows christening one-half of it Socket A and the other half Plug A, as if you really needed to distinguish between this socket and another one, as if this feature were perfectly normal and expected. No other socket or plug (or jack, or potentiometer) on the schematic is given a name. It doesn’t even trouble itself with distinguishing the Volume, Record Volume, and trimpot from each other. So, the only feature that is given a label is the one with no particular purpose at all.

Why did Wurlitzer abandon the modular system?

It is hard to know for certain. First of all, Wurlitzer was often caught between the professional and student uses of the electronic piano. Even the patent considers the modular unit a compromise between these competing interests:

“For use of the electronic piano simply as a piano, such as might be used by a student or in the home, or otherwise, the piano is used simply with one of the plug-in wave shaping circuits comprising the capacitor 204 and resistor 206. However, many persons, including those who would use such an instrument with a dance band, wish to obtain additional effects. This is done simply by incorporating the aforementioned controls in the music desk of the piano, and by plugging in the tremolo plug 250 into the socket 190, and similarly connecting the plug 366 and socket 218.”

Despite the patent’s insistence on the simplicity of the connections, there are some immediate and obvious complications with this plan. First of all, the auxiliary tremolo unit would require high voltage DC in order to operate, which would presumably be provided via Socket A. Should the consumer be trusted to make a connection like this? What if the consumer accidentally plugged the wiring harness for the tremolo controls into Socket A instead of the correct socket? Would the high voltage connections damage the controls? Would Wurlitzer need to develop a different type of socket to avoid the possibility of a hazardous mismatch? At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for electronics to expose consumers to dangerous voltages, but the Wurlitzer was more expensive and more lavishly engineered than the Bakelite radios and particleboard amps that were known to occasionally shock their users.

This September 26, 1959 article from the DeKalb Daily Chronicle (Wurlitzer’s home turf) reported 100 conventional and electronic Wurlitzer pianos in use at this music camp.

The practical considerations don’t end there. Would the tremolo module come stock with the keyboard, or would it be sold separately? Would the lid with the tremolo wiring harness come stock with the keyboard, or would that be sold separately? If the consumer or a school did not want the tremolo unit, could they buy a piano without the extra controls on the lid? What if they wanted to add tremolo later?

Are there enough dance bands and “persons [who] wish to obtain additional effects” to warrant the R&D necessary to manufacture the tremolo unit? Would a student or home user want to unscrew a dozen screws and reach inside the keyboard just to achieve a slightly different piano tone? In a sense, the ability to swap filters is actually a more advanced feature than tremolo, since total beginners usually don’t have the ear to appreciate the kind of subtle tonal distinction that a different capacitor value would offer.

The professional market is certainly more glamorous, but the allure of selling pianos to schools by the dozens was certainly just as tempting. The modular features had limited appeal to teachers and beginners, and would have increased the costs associated with selling the piano. Wurlitzer probably determined that it was more worthwhile to release a simplified piano that perfected the basic features that both beginners and professionals appreciate: decent feel, accurate tone, and portability.

What should I do with the mystery plug when I am restoring my amplifier?

We usually remove the pin 5 and 6 connections, and instead mount the required components inside the amplifier. They happen to be components that we typically replace anyway in the 112. Because the coupling capacitors are all ceramic, we swap them with new polypropylene caps. Ceramic capacitors can do funny things to the frequency response, and they are also more microphonic than other kinds of capacitors. For that reason, they aren’t a good choice in the signal path.

In practice, the octal socket in a Wurlitzer 112 amplifier has components mounted on each pin.

You may have noticed that, for a plug that doesn’t do much, it sure has a lot of stuff connected to it. Because the other pins do not connect to anything inside the plug, the original manufacturers of the amp used it to mount other components on — basically, as if it were a lug strip. If the plug was actually meant to be part of a modular system, this would of course be a bad idea. If you plugged in a different plug, the connections would interact with the components that you mounted randomly on the interior pins, possibly in very unwelcome ways. However, since there is no other plug that you can swap it with, using the plug as a lug strip is a good way to maximize available space inside the chassis.

When wiring point-to-point amplifiers, manufactures mounted components on every spare pin available. For instance, some tubes have more pins than they have internal connections. When you use one of these tubes, you’ll end up with an unused pin on the tube socket. Vintage amp manufacturers often used that pin as a lug — that is, an intermediate point on some completely unrelated connection. For this reason, you’ll sometimes glance inside of an amp and see some very strange things seemingly “connected” to the power tubes. Studying the pinout of the tube, however, you’ll see that the pin in question doesn’t connect to anything on the tube. For that reason, it is fair game to mount something on it. This is economical, since when you use the physical topography of the amplifier you cut down on the total number of lug strips that you have to use. So, even though Wurlitzer did not use the plug as part of a modular system, it still helped keep things organized inside the amplifier.

Further Reading

Browse all of our articles on restoring vintage gear. Or, click on an image below.