A Brief History of Student-Model Wurlitzer Electronic Pianos

Wurlitzer sold electronic pianos in bulk to schools from the very beginning. Today, the most common student-model Wurlitzers are the 206 and 206a, which correspond to the 200 and 200a. However, Wurlitzer sold electronic pianos to schools as early as the release of the Wurlitzer 112. Before that, they even sold conventional pianos to schools. Clearly, student pianos were an important part of Wurlitzer’s business model for decades.

Schools have different needs than professional or even amateur users, and how to weigh the interests of schools vs. everyone else was an issue that Wurlitzer repeatedly grappled with. There was certainly a thriving professional market for electronic pianos. For instance, Duke Ellington played one in a 1955 recording, and Wurlitzers were immediately popular with jazz pianists who had previously been stuck with poorly-maintained dive bar pianos.

However, schools could certainly have used a more convenient update on the conventional piano. Before $99 digital keyboards and mobile apps put piano basics within reach of total beginners, students who could not afford a regular piano had very few options. You could rent a piano, borrow one from a friend, or use a suitcase-like practice piano, which had a few octaves’ worth of realistic keys but no sound mechanism. People had to get creative in order to practice. As a child in the 1880s, legendary ragtime pianist Tony Jackson had burgeoning musical talent but no access to a piano. He made himself a harpsichord from scraps in the backyard; eventually, a few neighbors permitted him to use their pianos, in exchange for performing household chores.

The Wurlitzer 112 cost around $400 in the 1950s, the equivalent of over $3,000 today and about twice the price of a used spinet piano.[1] Technology would need to advance significantly before electronic pianos became what anyone would consider “affordable,” but the 112 was definitely a step in the right direction. According to one article,[2] outfitting a classroom with electronic pianos was half as expensive as buying conventional student pianos. Wurlitzer had a definite profit motive, but the need was clearly there.

Plus, Wurlitzer likely already had all the business-to-business connections and general know-how to sell pianos to schools. They had been doing this for decades. Even before the electronics age, Wurlitzer had been preoccupied with manufacturing ever-smaller and less expensive pianos. They were an early innovator of the spinet piano, a shorter and lighter style of upright piano. One 1922 Wurlitzer advertisement announced “The Miniature Piano with the Tone of a Large Upright,” the Wurlitzer Student Piano, “only half the size and weight of the ordinary upright”:

“The Wurlitzer Studio Piano has been universally accepted as the ideal school piano. It is only half the size and weight of the ordinary upright, but possesses a tone of marvelous volume and quality. [...] Two boys can easily lift it from the floor. There is plenty of knee space and the teacher can look over the top and direct the class while in the sitting position.”

In the 1930s and 1940s, Wurlitzer even had music schools in multiple cities across the United States. Clearly a loss leader for instrument sales, Wurlitzer Studios in Cincinnati advertised “8 Free Private Lessons on any Instrument” with “Instruments Furnished Free!”[3] In Kentucky, Wurlitzer offered free orchestra training “to every man, woman, and child who is able to attend rehearsals regularly Friday evenings from 7 to 9 o’clock.”[4] A 1946 advertisement for Wurlitzer Studios in Chicago claimed “250,000 successful students” (and noted that the Wurlitzer student band won the Chicagoland Music Festival “eight times out of nine”).[5]

Schools that had pianos often had dozens of them. In 1958, Ball State College inaugurated a new building for their music department by ordering 14 Wurlitzer electronic pianos for it.[6] One 1959 article counted 100 “Wurlitzer conventional and electronic pianos at a Michigan music camp.[7] One school system in Wichita, Kansas, purchased 24 Wurlitzers, set them up in a tractor-trailer, and tasked the instructor with driving the whole rig from school to school so that every third-grader in the district could participate in a piano class.[8] For Wurlitzer, bulk business-to-business sales were likely a surer bet than relying on the vagaries of the consumer marketplace.

Other perks of electronic pianos. The price of a Wurlitzer wasn’t its only appealing feature. Beginners need to practice scales and other repetitive pieces for hours. On a regular piano, this is annoying for everyone else in the household, as Dorothea Bump delicately explains:

“For those who are wondering what’s different about electronic pianos, let us hasten to explain that no home should be without one where there is a young player who must bang out scales and the Minute Waltz in practice sessions. This is a piano which may be tuned out so that only the slight click of depressed keys are heard by nearby listeners.”

Other teachers found that students felt liberated by the ability to play without their classmates listening. As told in the April 26, 1960 edition of the Fort Collins Coloradoan: “Mrs. Norton told the reporter that one second grader is even composing, partly, at least, because she has the courage to experiment when no one else can hear her on the ‘silent’ piano.”

Wurlitzer Student Pianos Through the Years

A photo in the November 9, 1956 edition of the De Kalb Daily Chronicle depicts students playing the Wurlitzer 112 in the classroom. The teacher is using an instructor module, possibly the Wurlitzer 820.

Model 112, 120, and 700 student pianos. During the 1950s and early 1960s, students used the same pianos that were sold in stores: that is, the same model 112s, 120s, and 700s. The teacher, however, had a master unit — the Wurlitzer 820 — that fit on the piano lid and contained a microphone and other controls. The 820 connected to the teacher’s record input and speaker jack. (The music rack had to be removed to accommodate use of the 820, which probably explains at least some missing music racks today.)

The 820 also connected to student pianos via a long cable that snaked around the room. At each piano, the cable terminated with a plug that 1) connected to the next piano’s cable, and 2) forked off into a 1/4” instrument cable that connected to the piano’s speaker jack. Up to six pianos could be connected together, and four sets of six could be connected to the 820, for a total of 24 keyboards per classroom. (Every subsequent teacher model had a maximum of 24 student connections as well.)

On the face of the 820, there was a microphone and two rotary switches. The first switch had 24 positions, each one corresponding to a student’s piano. The teacher could use this switch to select a single student’s piano, listen to that student play, and give him or her instructions through the microphone. The second switch was for listening to or communicating with six-piano groups of students. The volume of the microphone was controlled through the input volume on the 112, or via the regular volume control on the 120.

Each student wore headphones that plugged into the regular headphone jack. The teacher had a special one-sided set of headphones, so they could keep one ear free to listen to the classroom generally. The headphones during this era were extremely rudimentary: more like two tin cans tied together with a string than modern headphones.

The 146 and 726 student pianos. With the release of the 140-series, Wurlitzer created parallel models of student pianos: the 146b (the portable version of the 140b) and the 726 (the console version). These keyboards were almost exactly the same as the originals. They contained the same mechanical action and the same amplifier packaged in the same cabinet. The only differences were:

The 726 cheek block contains switches that aren’t found in non-student model Wurlitzers. Note the cable, which leads to the hardwired headphones.

Although the vibrato components were present in the amplifier, vibrato itself was absent in the student models. Reconnecting the vibrato in a 146b or 726 is very simple, however.

The entire cheek block of these student models is different. The 140b/720b has a volume control, a vibrato control, and a headphone jack in the cheek block. The 146b/726 has a volume control, but in place of the vibrato control there is a “self/ensemble” switch, and in place of the headphone jack there is another switch that toggles between headphones and the onboard speaker. The self/ensemble switch probably allows students to switch between listening to the entire classroom, or just their own piano.

On student models, the headphones are hardwired into the keyboard. The headphone cable comes out of the cheek block. This is a little annoying because, if you remove them, you’ll be left with a tiny hole. (Maybe one day we will find a reason to mount a mini-switch there?) The headphones themselves are more similar to modern headphones than the previous Wurlitzer models, which were basically just empty plastic cups that directed the sound into your ears.

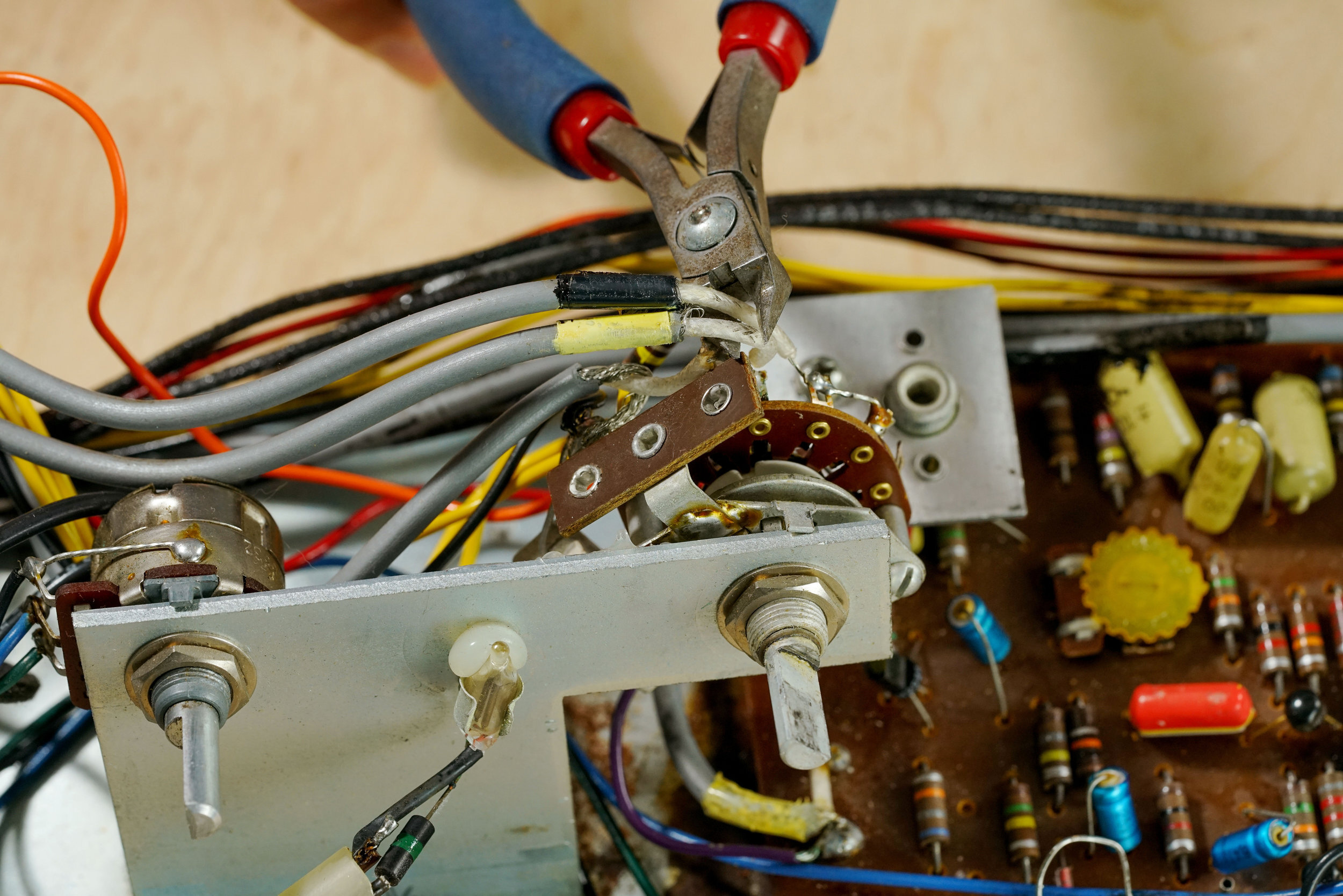

Each student model contains two ports in the back. This was how each keyboard connected to the next, and ultimately to the teacher’s keyboard. There are several pins on the port, some of them with mains voltage across them, so if you have a 146b or 726 you should completely remove all of these connections.

The teacher model appears to have been a regular 146b or 726 that connected to the rest of the classroom using a Model 830 teacher module. Steve Espinola has reported unsubstantiated rumors of a stand-alone teacher model 147 (the name is analogous to the 207/207a), but he has ultimately concluded that this model is “mythical” since nobody has ever produced any evidence of its existence.

Wurlitzer 206 and 207. There are a lot of student-model 200-series Wurlitzers, but we will only discuss the 206/207 and the 206a/207a. The other models are extremely similar and typically only have minor differences, like extra outputs or a different colorway. If you are interested in learning about the full complement of student pianos, Steve Espinola’s website has more information.

The 206 is the first instance of a dedicated student-model Wurlitzer. It is a console Wurlitzer on feet (as opposed to casters) and has a similar silhouette to the 203. However, where the 203 has an uninterrupted speaker baffle on the face of the cabinet, the 206 has a shelf for storing the headphones.

The speaker situation is different depending on whether the 206 is a late or early release:

This is an early 206 (with a later music rack). As you can see, there are no speakers mounted in the front baffle.

Early 206 Wurlitzers have two 4x8” speakers mounted on the amp rail, exactly like the 200. Lacking speakers, the face of the cabinet is tolexed (as is the back). Inside, the cabinet is mostly empty and only contains the two ports that connect the 206 to other student Wurlitzers in the classroom.

Late 206 Wurlitzers have two 8” speakers mounted in the cabinet, both in the front baffel, which is covered in beige speaker cloth. Unlike the 203, there are no speakers in the back of the cabinet, which is covered in beige tolex. Like the 206, the 206a has two ports on the back.

The 206 amplifier was the same as the 200: same circuit board, same components, etc. The only difference is that the vibrato circuit was disabled with a jumper wire, and in place of the vibrato control the keyboard had a self/ensemble switch. Also, the aux output was not present. But because the amplifiers were complete 200 amplifiers, and the vibrato circuit was only disabled and not removed entirely, it is very easy to bring a 206 amplifier up to 200 specs.

In the 200-series release, the teacher module was phased out. Instead, the teacher used a Wurlitzer 207, another beige console keyboard that contained all of the necessary controls in a panel positioned above the keys. The 207 connected to the student pianos with a series of four ports on the back. Each port could accept an “ensemble” of up to six student pianos.

The 207 also coincided with the release of the Keynote Visualizer, a tool intended to help students learn to sight-read. The face of the Visualizer had a music staff and a diagram of the piano keys. It was mounted on the 207, and connected via a port on the side. When the teacher played a note, a bulb would light up the image of the key corresponding to the one the teacher played, as well as the corresponding position on the staff.

The 206a has similar colors, but there are two speakers mounted in the front baffel. This model also has only one shelf (rather than the two cubby-like shelves on the 206), where the inputs and outputs are located.

Wurlitzer 206a and 207a. With the release of the 200a, Wurlitzer correspondingly updated their teacher and student models. Cosmetically, very little changed. They keyboards were still beige consoles, with beige speaker cloth, and two 8” speakers mounted in the front of the cabinet. The 207a contains a very similar control panel to the 207. The main difference between this new model and its earlier iteration is the amplifier.

The 200a amplifier — which both the 206a and the 207a contain — was very different than the 200 amplifier. If you compare them side by side, there are even obvious physical differences. The 200a’s components are much smaller than those on the 200, and the circuit board has a tighter and more organized layout. These things can be attributed to fast-paced developments in solid state technology at the time.

Now, the amplifier has dedicated circuitry for each of the 200a’s applications. The preamp and power amplifier circuits are identical to all 200a-style models. However, three circuits — the vibrato, aux output, and mike preamp — do not appear in every keyboard. But because all Wurlitzers use the same circuit board, the connections on the bottom of the board are present regardless of the model. If the Wurlitzer does not include that feature, only the components will be missing.

So, the Wurlitzer models 206a and 207a did not contain vibrato or an aux output. These areas on the circuit board will be empty and their holes are unlabeled. However, they can be repopulated with the required components at any time, because the circuit connections are all present on the bottom of the board. Conversely, the 206a has the mic preamp section populated, but on a Wurlitzer 200a this area of the board will be empty.

The Wurlitzer 214a/214va was actually a student/teacher model that contained all of the circuitry, even vibrato. If you have a 214a or 214va, you may have noticed that the amplifier contains all possible components, with no blank areas on the circuit board.

As for the Wurlitzer 207a, it worked similarly to the 207 teacher model. It also had a front panel that contained the same types of controls. The Keynote Visualizer was updated as well, but connected in a very similar way.

Notes

[1] One Wurlitzer advertisement in the October 9, 1960 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer advertised a Wurlitzer 120 at the sale price of $369 alongside a $125 used upright piano, a $245 used spinet, and a $525 Baldwin Acrosonic. However, used electronic pianos were often available in the $200 range: one music store in Rapid City, South Dakota, advertised a used Wurlitzer electronic piano for $225 in the April 7, 1960 edition of the Rapid City Journal. As a side note, electronic organs were consistently more expensive than electronic pianos: the Wurlitzer Spinette organ was listed in the same Cincinnati Enquirer advertisement for a sale price of $975.

[2] In “Ball State Installs New Electronic Pianos for Soundless Teaching,” columnist Dorothea Bump offers a list of the Wurlitzer’s good qualities: “The 64-note keyboard instrument is priced at about half that of regular pianos, stays in tune, plays beautifully under any conditions of cold, heat, or humidity, and has a radio-record player plug-in jack so the pianist can play along with recorded or radio music.” (Muncie Evening Press, Feb. 15, 1958)

[3] Found in the September 13, 1931 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer.

[4] Found in the October 28, 1934 edition of the Louisville, Kentucky Courier-Journal.

[5] Found in the August 18, 1946 edition of the Chicago Tribune.

[6] See the article referenced in Note 2.

[7] “Music Camp Once Again Makes Piano News,” from the September 26 1959 edition of the DeKalb, Illinois Daily Chronicle.

[8] As reported in the Danville (Virginia) Register on March 23, 1967: “The Truck Gets a Rondo: Music is the Cargo When This Tractor-Trailer Goes to School.”

Further Reading

Browse all of our articles on restoring vintage gear. Or, click on an image below.